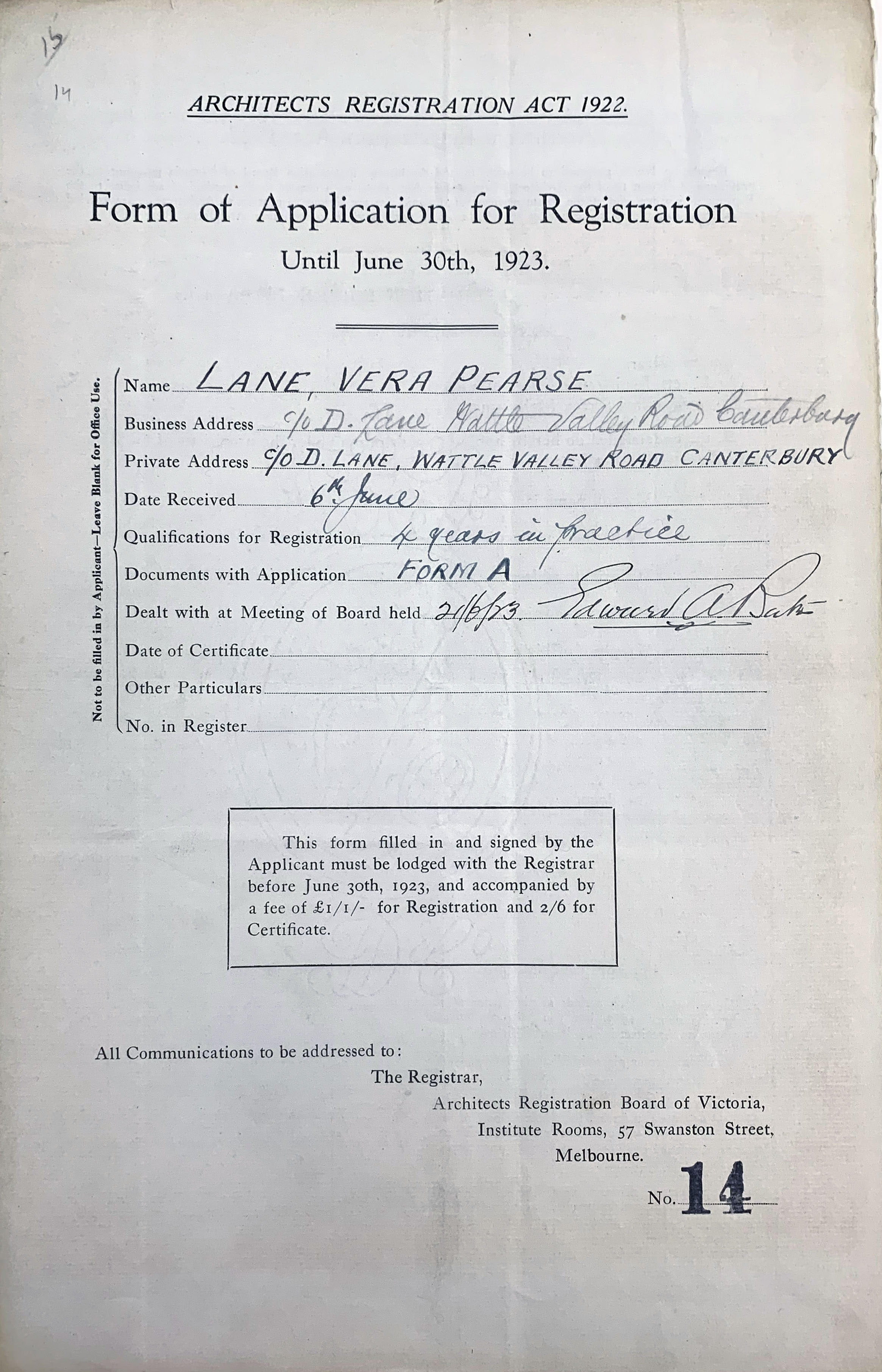

Vera Pearse Lane (1896-1979) became the first woman to be registered as an architect in Victoria, when she was the fourteenth candidate registered under the Act in June 1923.

Her architectural education had begun in 1917 when she enrolled in the newly-invigorated Diploma of Architecture course at the University of Melbourne – only the fourth woman to commence. Concurrently (as was usual), she began articles with Alec Eggleston. She graduated Dip.Arch in April 1921, the second woman to obtain the degree (after Eileen Good in 1920) and the thirteenth candidate overall. The same year, she studied at the University of Melbourne Architectural Atelier: a design-focused school aimed at educating newly qualified architects the finer aspects of composition using Beaux-Arts principles and based on similar offerings at the Architectural Association in London. At that time, the Atelier did not offer a formal qualification, although this would later follow in the form of a Diploma of Architectural Design, and eventually be absorbed into the five-year Bachelor of Architecture program. Lane passed the Royal Victorian Institute of Architects’ Professional Practice examination in 1921, and was elected as Associate of the RVIA the following year.

Lane was the eighth and last of James and Jane Lane’s children. The family were comfortably middle class, with sons entering professions and daughters marrying well. Her father had been a teacher, and presumably encouraged education for his children: Lane herself had taken matriculation subjects over several years at Methodist Ladies College, Melbourne, before entering university, and it may have been with her father’s support that she took up architecture. The sudden death of James Lane in 1922 whilst visiting family in New Zealand, however, may have altered her prospects for a career. She was in London at the time she first registered, and over the next seven years, she travelled from Melbourne to London in company of her mother and sisters at least twice for extended periods, maintaining her Institute membership until 1928 and registration until 1931. It is unknown whether she was undertaking projects or working in a firm through this time, although it seems more likely that her primary duties were as travelling companion to her ageing mother. Her return to Australia in 1930, with the Great Depression weighing on prospects and income, resulted in her surrendering her last links with architecture, and she lived quietly with one of her sisters for the remainder of her life.

Lane’s situation reveals the social pressures on women at the time. Even with supportive families, personal circumstances (marriage and children, or dependent relatives) usually translated into women having to give up professional ambitions in favour of caring duties. The formalisation of architectural qualification through degree courses, institute examinations and registration (that were regulated and standardised), as well as the upheaval of the First World War, made it easier for women to enter the profession. At the same time, social pressures, the difficulties of gaining employment in sympathetic firms, and economic circumstances made success hard to achieve. Nevertheless, by 1924, six women were registered architects – just over 1% of the total number on the register. This number remained steady until the late 1930s, when the number and percentage of registered women architects began to rise. From that time, the numbers of registered women architects approximately doubled every ten years: 10 in 1940; 23 in 1950; 44 in 1960; 74 in 1970; 125 in 1980; and 226 in 1990.

Updated