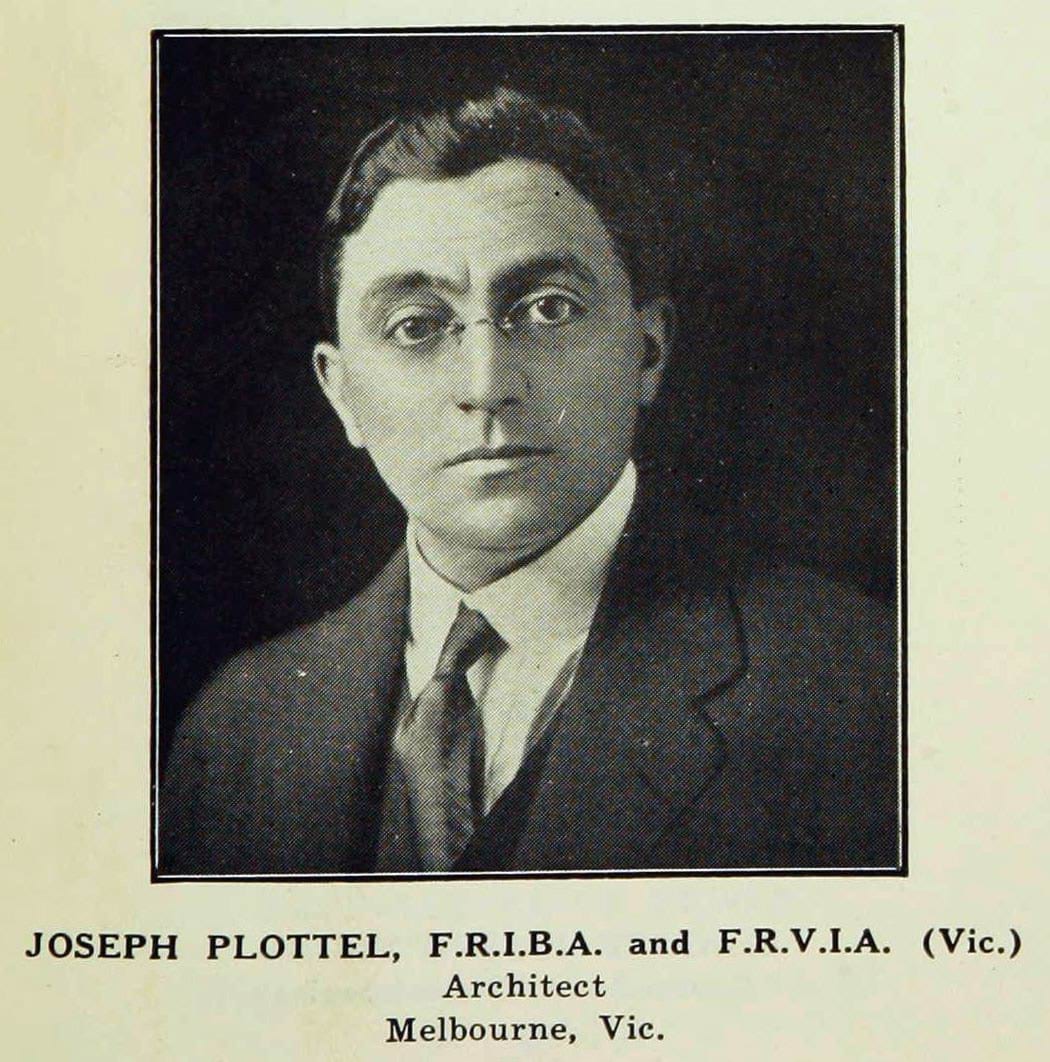

Joseph Plottel (1883-1977) was the 73rd registered architect in Victoria. He was descended from Russian Jews, who had likely fled to England as the result of pogroms in 1881-82 and settled in Middlesborough, Yorkshire. Plottel was born soon after his parents’ marriage in 1892, the eldest son of Philip and Sarah. Philip emigrated to Melbourne in 1888, a jeweller by trade, with Sarah and children following in 1890. The family settled in St Kilda, but Philip’s early death at 32 in 1893 prompted a return to Sarah’s family in Yorkshire soon afterwards.

Plottel was articled to architect and surveyor Robert Moore of Middlesborough in 1899. On completion of his articles, he travelled to South Africa in 1903, where he worked for nearly four years. This included stints in Johannesburg, Pretoria (where he was a draftsman in the Public Works Department) and Cape Town, in the City Surveyor’s Office. In February 1907, he arrived in Melbourne, pausing an intended journey to San Francisco because of lack of funds. His previous public works experience stood him in good stead, as he became a draftsman with the Victorian Railways. In 1910, he resigned from that position and opened his own office in Prell’s Building, Queen Street. There is a suggestion that Plottel worked briefly for the well-established Melbourne Jewish architect Nahum Barnet around this time, although it is not clear this occurred. Regardless, they were undoubtedly acquainted, and Barnet was likely a mentor to the younger architect. Plottel contributed his fair share of support to other practitioners by providing facilities, allowing other architects to use his office to advertise tenders, including architect Benjamin W Tapner in 1910 and Harold E Bunnett in 1912. Bunnett worked in association with Plottel in 1914, continuing in the firm thereafter as associate or partner, the firm being Plottel, Bunnett & Alsop (1927-29); Joseph Plottel (1930-51); and finally Plottel, Bunnett & Associates (1951-c1960).

Plottel soon took on significant projects that included residential flats, city buildings and industrial complexes. Early works included the Clarendon Flats in East Melbourne (1912), Embank House on Collins Street (1911, dem.), and the Maize Products Factory in Footscray (1912). In 1914, Plottel (in association with Bunnett) won the competition for the Williamstown Town Hall and Municipal Offices. The design was in the then-popular Edwardian Baroque style, with a tower, domes and rusticated façade. However, the project became mired in internecine municipal politics, with a fee dispute between the architects and council, in which the latter prevailed. A scaled-back project by Plottel and Bunnett to house municipal offices, with rusticated panels interspersed with red brick sections, was then built.

By the 1920s, Plottel regularly undertook prominent projects across Melbourne and beyond, maintaining a Canberra office in the late 1920s; its major project was the Manuka Arcade (1926). He undertook Masonic projects, including the Masonic Hall, Newport (1925) and Masonic Club building, Flinders Street (1926), and a series of recreational facilities: the Yarra Yarra Golf Club, East Bentleigh (1928), the Victorian Club Building, Queen Street (1928), remodelling of the Riverine Club, Wagga Wagga (1930) and the Hepburn Springs Hotel (1934). His St Kilda Synagogue (1926) and Temple Beth Israel, East St Kilda (1937) were both bold designs in brick, the former a crisp Byzantine style with a shallow copper dome and the latter a sharp-edged Moderne block. Plottel revisited his interests in the Byzantine and Mediterranean styles with his design for the Footscray Town Hall (1936). The BYFAS (Bradford Yarra Falls Austral Silk) Factory (1937) in Abbotsford demonstrated his extraordinary design skills, with inventive use of brick patterns and planes to create lively façades on an otherwise utilitarian building. Plottel’s firm continued projects well into the 1950s.

Many of Plottel’s clients were also Jewish and these connections had helped the young architect establish himself in private practice. Architects regularly drew on their religious, social and professional networks as a source of clients and projects. Connection to a religious denomination often brought work for the church or synagogue; membership of associations such as masonic clubs brought similar opportunities; and previous experience in public service usually enabled employment in government agencies, regardless of their location.

Prepared by Professor Julie Willis of the University of Melbourne

Updated