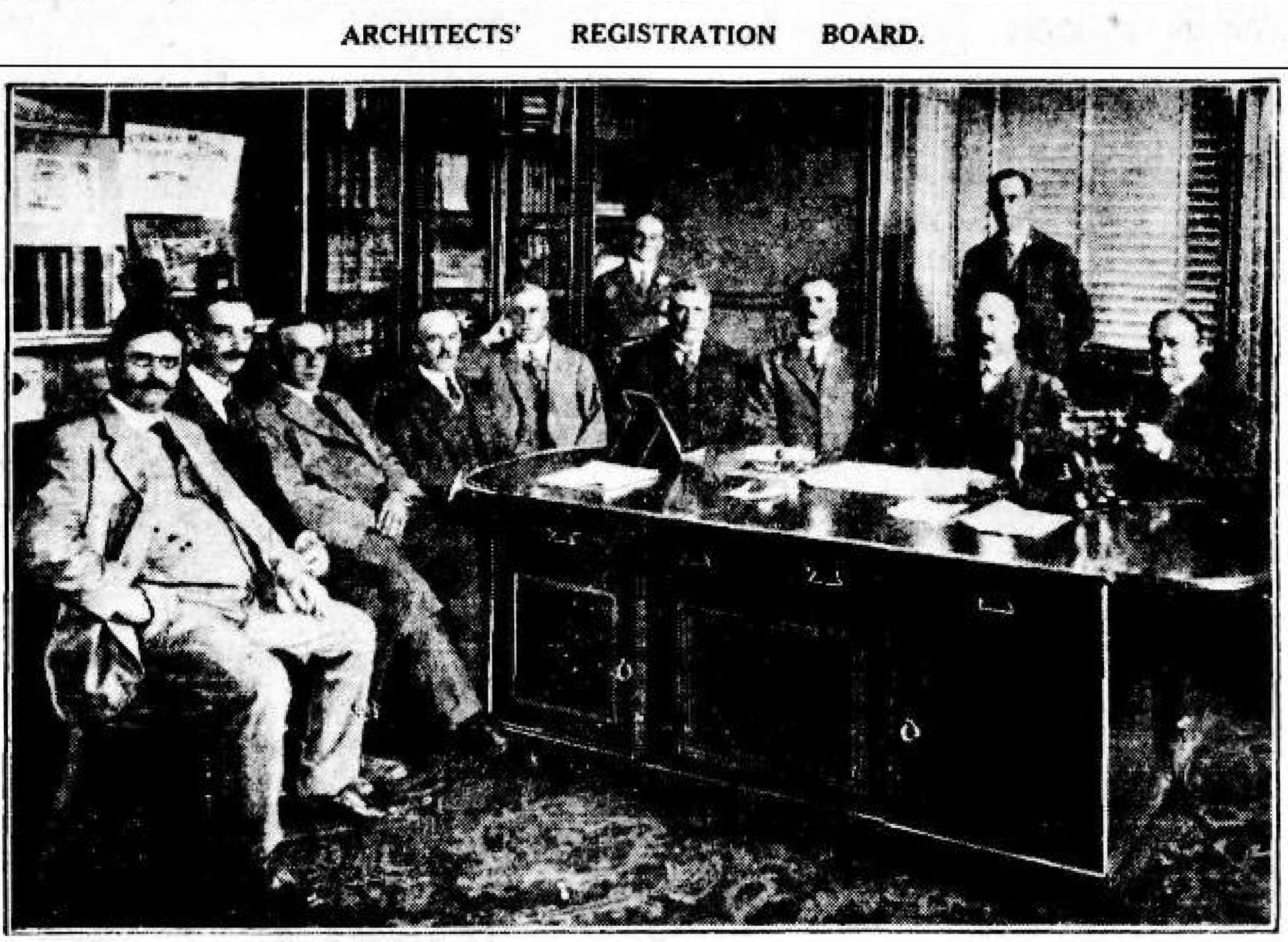

The passing of the Architects’ Act in 1922 meant both the establishment of a procedure and maintenance of a register of architects, and a governance structure to oversee it. Under the Act, the Architects’ Registration Board of Victoria was to consist of seven members, being: two nominated by the Royal Victorian Institute of Architects, and thereafter by the body of registered architects; one by the University of Melbourne; one by the collected bodies representing engineers in Victoria; and the remaining three by the Governor-in-Council. The Board elected its own Chair and was empowered to appoint a Registrar and any such other administrative staff to be able to manage the registration processes and documentation.

In late March 1923, the first members of the ARBV were duly appointed: Edward A Bates and WSP Godfrey (RVIA); John S Gawler (University of Melbourne); Henry Morton (representing engineers and surveyors); and E Evan Smith, George R King and Kingsley A Henderson. At their first meeting in early April, Bates was elected Chair, and William M Campbell appointed Acting Registrar. From its inception, the Board depended heavily on the experience and administration of the RVIA to provide the scaffolding of the new entity, as Bates, Godfrey, and Henderson were all current or recent members of the RVIA Council, and Campbell its honorary secretary. Other ARBV appointments brought together key leaders across the profession: Morton had previously been the City of Melbourne Architect, and, at appointment, its City Engineer and Surveyor; and Smith was Chief Architect of the Victorian Public Works Department. Gawler was lecturer in architecture at the University of Melbourne, as well as being a partner of Gawler & Drummond; and King headed architecture at the Gordon Institute in Geelong.

The apparent entwining of the RVIA and ARBV continued for decades through shared facilities and personnel, as the Board was accommodated in the RVIA offices in Swanston Street, a space shared with the Victorian Institute of Engineers (VIE) and Victorian Institute of Surveyors. In the beginning, this had made sense: the RVIA offered a ready-made administrative structure and location that the fledgling ARBV could leverage to create a resource-efficient agency. There was no real evidence, based on the broad acceptance of practitioners from diverse education and experience backgrounds, that the RVIA members were seeking to closely define the registered profession in their own image. Nevertheless, the Board and Registrar positions were dominated by RVIA office bearers for nearly fifty years. Campbell, for instance, was succeeded as Registrar by John B Islip in 1930: Islip had been appointed the RVIA’s secretary (an employee, rather than a member of the RVIA Council) in 1927. Islip would hold the position of Registrar until his retirement in 1970, apart from a break of service during the Second World War due to military service.

The early decades of the ARBV were dominated by long periods of service: Godfrey served more than twenty years (1923-1945); Gawler, even longer (1923-1946); Percy Everett, Governor-in-Council nominee and PWD Chief Architect, nearly twenty years (1935-1954); Stanley T Parkes, nominee of the registered architects, served over thirty years (1932-1965). Others with long tenures included: Kingsley A Henderson (1923-1939); George R King (1923-1934, 1939-1940); and Professor Brian B Lewis, Dean of the Faculty of Architecture at the University of Melbourne (1947-53, 1956-1970). AC Leith, the engineering societies’ nominee, served an astonishing thirty-five years (1928-1967, apart from war service 1942-45). Leith’s appointment demonstrated the closeness of the VIE to the architecture profession and the blurred nature of professional boundaries at that time: he was honorary secretary to the VIE, and a graduate from the Bachelor of Civil Engineering at the University of Melbourne, but practiced as an architect-engineer.

The location of the ARBV remained alongside the RVIA (later Royal Australian Institute of Architects (RAIA) Victorian Chapter), Institute of Engineers and Institute of Surveyors. The three institutes had formed the Allied Societies Trust Limited in the early 1920s and by 1925, were actively seeking to purchase a site in Melbourne. The Godfrey & Spowers-designed Kelvin Hall – Godfrey being on both the RVIA Council and ARBV at the time – opened in 1927 in Exhibition Street, and was home of the three institutes and the ARBV for the next forty years.

By the time the Allied Societies Trust was disbanded in 1969, the tight alignment between the RAIA and Registration Board had begun to fade. Although the ARBV would continue to co-locate with the Institute for another fifteen years, it was increasingly a distinct entity. Registrars after the Islip era were independent appointees without the same level of intimate connection to the profession: these included John Janicke (1970-71); Tom Cranston (1971-72); Raymond Wilson (1972); Noel Bewley (1972-86); Mary Mauthoor (1986-1992); Jeffrey Keddie (1992-1998); Michael Kimberley (1998-2008); Alison Ivey (2008-18); Adam Toma (2018-2020); Allan Bawden (as Interim Registrar, 2020-2021); and Dr Glenice Fox (2021-). After being co-located with the Institute in St Kilda Road and Howe Crescent, South Melbourne, in 1987 the Board moved to its first independent location in Drummond St, Carlton. In 2000, it moved to Nauru House in Collins Street; to Albert St, East Melbourne in 2005; and then to its current location in Little Lonsdale St in 2021.

Board membership tenures tended to be shorter from the 1960s onwards, but still included key leaders of the profession and leading practitioners, such as Peter McIntyre, Ron Lyon, Rod MacDonald, Harry Winbush and Peter Williams. When Sue Dance was appointed to the Board in 1983, she became its first female member in its then sixty-year history.

The introduction of the revamped Architects’ Act in 1991 saw the first significant change to the structural composition of the ARBV. Some amendments were corrections to historical anomalies built into the 1922 Act, such as changing the exclusive nomination of a member of the Board from the University of Melbourne to be a nominee from the then-three approved schools of architecture in the State. The membership of an architect in senior government service was affirmed, regularising what had been long-standing practise. The body of registered architects still had two positions, the allied engineering and surveying professions retained a nominee, and the RAIA (Vic Chapter) formally gained a nominee to the Board. In a distinct change, two board positions were reserved for individuals representing consumer interests, to be nominated by the Minister responsible for administering the Consumer Protection Act, bringing the total membership to eight. The focus on consumer protection reflected aspects of the torrid debates that had led up to the 1991 Act, ostensibly to encourage increased competition and discourage the potential for cartel-like behaviour amongst architects, particularly with regards to fee-setting.

In 2005, the Board was extended to ten members, incorporating, for the first time, two members representing the building industry. In retrospect, this change filled an obvious gap in the representation on the Board: it had long incorporated membership from architectural education, the profession itself, the allied professions of engineering and surveying and, latterly, the consumer, but not the professionals who constructed the works that architects designed.

In 2024, the composition of the Board will change again, requiring a minimum of three members and a maximum of nine. The changes are significant as, for the first time, they remove all representative positions. For the first time in its 100-year history, the ARBV will not explicitly seek members from the Australian Institute of Architects, the combined schools of architecture, or the allied professions, although it is required to have at least three architect members. Instead, its Board will be made up of members who need to bring a range of skills relevant to the work of the ARBV, including what might be regarded as standard skill sets for company directors, such as risk management, governance, communications, financial management, and strategic planning; as well as knowledge of the regulatory requirements of the building industry and architecture.

Prepared by Professor Julie Willis of the University of Melbourne

Updated